This article is by Bradshaw Advisory senior consultant economist Lizzie Pinder.

The UK’s slow growth is concerning with competitor economies seemingly climbing out of the COVID-induced growth slump more easily. So where does the trade deficit come into all this? Is it important?

A trade deficit, put simply, is the difference between what we sell as a country and what we buy - we import more than we export, so this is a deficit. They can be damaging due to the implied reliance on foreign borrowing to finance consumption and investment. Trade deficits can also be a sign that a country’s domestic industries are not competing well internationally. They are also not all bad news though. Trade deficits can support economic growth if businesses are importing more to boost production for example. The US, the world’s largest economy, has run a deficit since the 70s.

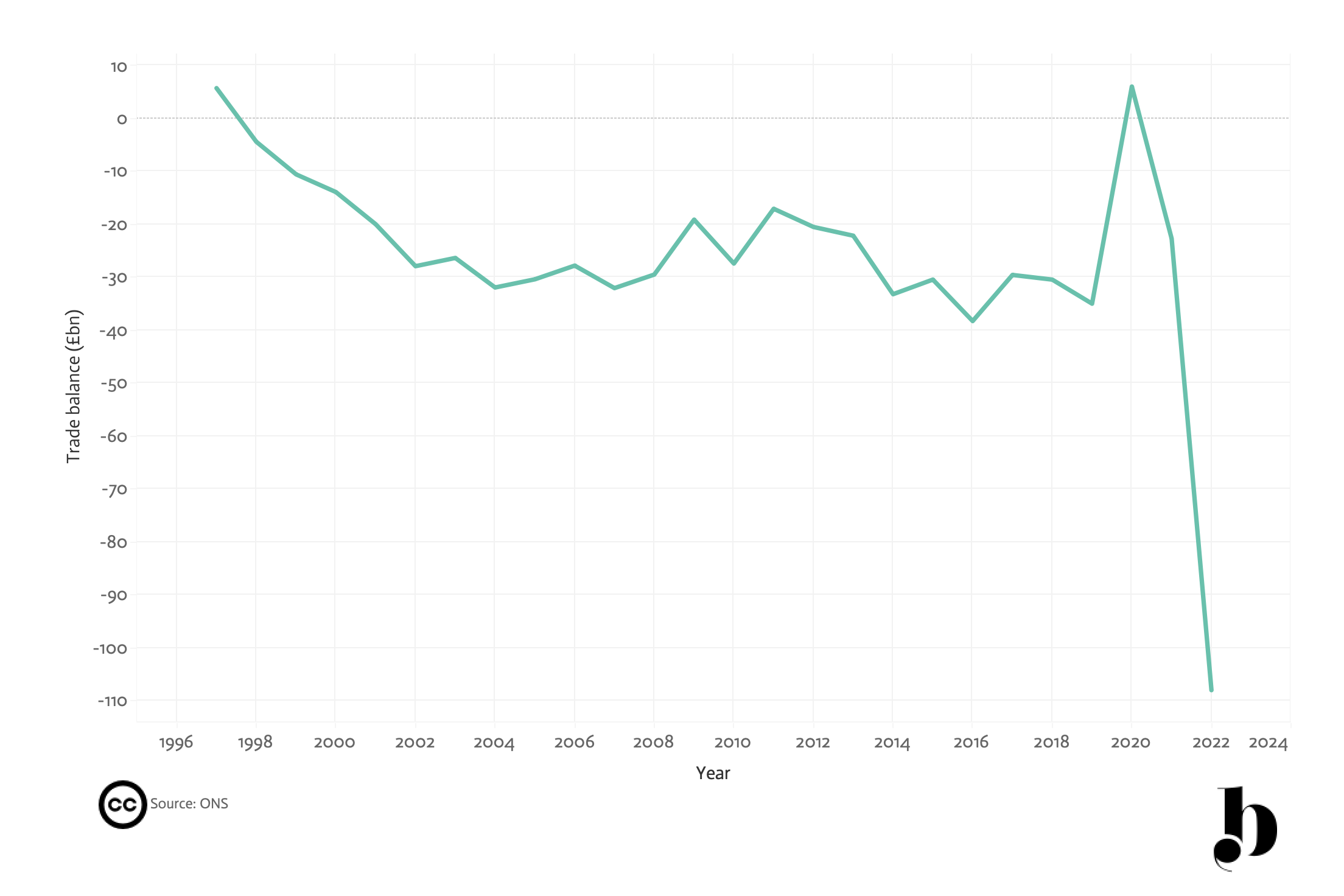

In 2022, the UK trade deficit rocketed to £108 billion, the highest level since records began. It is the stated aim of our government to boost our exports and get more businesses exporting to support growth, employment and help level up our country. Yet, our current trade deficit is triple the size of the 2016 deficit - the second highest on record.

Classic comparator countries like France, Germany and the US rode the wave of booming exports post pandemic but the UK has been left behind. Why are we taking so long to recover, what damage has been done and what needs to happen next to improve the UK’s longer term trading performance?

The government target (renewed this year, after failing in 2020) to boost the export of goods and services to £1 trillion by 2030 is set to fail again. Export goods and services have risen since pre pandemic levels: £781 billion in 2022 versus £672 billion in 2018. However, the Government forecasts exports to drop to £707 billion next year and has pushed back the £1 trillion target to 2035. This is driven by global and national economic struggles and trade barriers such as red tape which limit export performance. The UK also has a structural problem when it comes to exports. It generally runs in a trade deficit, dependent on imports, largely due to cheaper production costs abroad.

Figure 1: UK annual trade balance (£ billions)

Figure 2: UK quarterly trade balance (£ billions)

What caused this trade shock?

A perfect storm. Brexit, a worldwide pandemic, a European war, a disastrous mini budget. Should we be surprised that UK trade has seen such a marked slump?

The 2017 Brexit announcement triggered the start of the decline. The global market’s loss in UK confidence prompted a sterling devaluation. This escalated relative import prices, resulting in climbing import dependent production costs and shrinking (export) production. Brexit hit UK exports to the EU initially, but they recovered quickly, rising from £171 billion in 2019 to £195 billion in 2022.

Mysteriously, the damage has been to exports to non-EU countries, despite Brexit campaign promises to open the UK up to global trade. Meanwhile, other G7 countries' exports are booming. Available data doesn’t tell the whole story but surging post pandemic US demand for electronics (which are not the UK’s comparative advantage) explains part of it. A dive in UK road vehicle and crude oil exports to China and organic chemicals to the US contributed to a further £2 billion trade deficit widening in the final quarter of 2022.

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic actually eliminated the UK trade deficit due to a sharp fall in trade, where exports fell and imports plummeted even further. In 2021, the trade deficit climbed again, as importing started to return to pre-pandemic levels.

Disruption to Russian gas supplies doubled the total cost of gas and fuel imports in 2021 and in 2022. The cost of total UK food imports grew by a fifth in 2022, driven by global food price inflation. This is a result of pandemic and conflict prompted disruptions to supply chains and inflated energy prices raising fertiliser, production and transport costs. Brexit induced non-tariff trade barriers such as customs checks haven’t helped either.

What damage has been done?

2022 saw the highest levels of inflation in 41 years. Import inflation played a major role - stifling real wages and exacerbating the cost of living crisis.

The slump in exports dampers business revenue. Inflation amplifies capital costs and squeezes margins further, limiting business investment and economic output. Increased interest rates for loans through monetary policy, while appropriately introduced to curb inflation, create an extra weight on businesses and consumers.

What’s more, UK economic growth plummeted below large economies like Germany and the US, to -9.3% in 2020 and is recovering slower. Falling labour market participation, import inflation and UK vulnerability to gas prices due to high central heating use have all played a part.

What to do next?

Recovering our trade performance is a tall order for the government to tackle. Alongside resuscitating the NHS, recovering from the mini budget and solving an energy crisis, while addressing mounting government debt.

The spring budget was the government's chance to set out policies and promote confidence in the UK to solve and mitigate these existing issues lingering in the UK economy. Supporting business recovery and maximising production was key. Jeremy Hunt downgraded the expensive super-deduction policy (130% relief on first year business investment) to 100%. This won’t help the terms of trade shock in the short term, but it is probably necessary, given the magnitude of public spending demands.

The announced customs package to simplify exporting and importing procedures goes some way to support exporters. But financial incentives for exporters, such as export tax credits could give the UK the boost it really needs. While, announcements to invest in UK R&D and technology should support the long term export strategy through developing highly skilled services.

Import substitution, through targeted domestic production to reduce buying from abroad, is vital for this import reliant nation’s comeback. Should consumers expect access to the full range of global produce throughout the year? Local production and consumption would buffer global price inflation and reduce air miles and Brexit import disruptions. And the benefits of maximising the UK’s renewable energy potential are endless.

Will the UK recover from this terms of trade shock? The OECD forecast the trade deficit to reduce by 35% in 2023. Although this is an improvement, it still maintains the deficit way above historical levels. Recovery depends on global efforts to control inflation; the government’s ability to recover trade performance and the avoidance of further negative shocks. Let’s hope that this is a blip caused by the national and international shocks mentioned above and the UK can recover.