In, out, in, out: what is raising income tax while cutting NI all about?

Our founder and CEO Tom Lees and Chief Economic Adviser Andrew Morrison take a look ahead to the upcoming Budget and the state of UK finances.

It’s almost Budget day in Westminster! How can you tell? So many kites have been flying from No.1 Horse Guards (mooting tax changes) that you can barely see the sun!

The Chancellor’s challenge is a £20-40bn fiscal gap: caused by poor growth, poor productivity, increased spending, high inflation, high borrowing costs, and an inability to cut spending without sparking a backbench revolt.

With two weeks to go, the most likely of the 100 plus money raising ideas floated by the Treasury seems to be an increase in income tax rates, but crucially done while cutting national insurance (NI) at the same time.

What is this ‘hokey-cokey’ fiscal approach all about? And what will it achieve? Before we answer that, first let’s set out some context and take a look at the state of the UK’s finances.

Follow the money

In the last five years, UK borrowing costs (the cost of 10-year UK gilts) has gone up by fifteen times - from 0.3% to 4.4% - meaning substantial costs for any new borrowing.

UK 10-year borrowing costs (source: Bloomberg)

The UK’s borrowing costs are now the highest among major developed economies:

UK government borrowing costs remain higher than other major developed economies, with 10-year gilt yields now above 4%.

The UK currently spends around £1.3 trillion (£1,279bn to be more precise) a year while bringing in £1.1 trillion (£1,141bn) in tax receipts. This means a deficit (gap between income and spending) of around £140bn. We need to borrow this from the financial markets, made up of individuals and companies that buy our debt for a certain ‘interest rate’ (or yield in the parlance). A ‘black hole’ of £30bn would be around 2.5% of current spending.

In 2024-25, the OBR calculated UK debt to be equivalent to 96% of national income. That is £2.8 trillion or £98,000 per household. That is a lot of debt!

In terms of day-to-day spending, around half of all spending goes on the NHS, social care and welfare (including pensions):

£310bn on welfare and benefits

£205bn on health and social care

£95bn on education

£60bn on defence

£28bn on transport

£20bn on the Home Office

£12bn on homes and communities

£7bn on environment, food and farming

£105bn on debt interest payments (more than education or nearly three times transport spend)

Tax the rich?

In the run up to the budget, following her failure to cut welfare spending, the Chancellor has faced calls from her backbenchers to raise taxes on the rich. Over the summer, ‘JUST RAISE TAX’ was proudly run on the cover of the New Statesman. During his brief moment in the limelight this summer, the forever wannabee Labour leader, Andy Burnham’s new ‘Mainstream’ group also called for wealth taxes. Further to the left, the charismatic populist leader of the Green Party has also been banging the drum to raise taxes on the super rich. Is this a silver bullet or are we missing something?

Firstly, most of our tax receipts come from three sources: income tax, national insurance and VAT. Together they account for £650bn of revenue or around half of all tax and duties taken in by the UK.

29% of all income tax is paid by the top 1% of earners and around 10% is paid by the top 0.1% of earners.

In overall terms, the Treasury produces something called ‘distributional analysis’ that shows the impact of taxes and public spending across different income groups. As you can see from the chart produced at the Spring Statement (March 2025), two points stand out:

60% of the population (the first six deciles) receive more in welfare and public services than they contribute through the tax system.

The top decile (i.e. 10% highest earners) pay about 60% of their net income in taxation (in all its forms) and receive just over 15% back from public services/welfare.

Taxes and public spending by income decile, 2028–29

According to the Sunday Times Rich List there are 156 billionaires or billionaire families in the UK who are estimated to have c.£700bn or so in wealth. Let’s imagine we were somehow able to get hold of 100% of this money (extremely unlikely as billionaires are very mobile and good at moving money around) would only keep the country running for a mere six months. Then what would we do? Say instead we take 10% of the billionaire’s wealth and get £70bn, that still leaves the UK in a deficit of £70bn a year we need to borrow or raise from somewhere else.

There is a fundamental mismatch between how much people think things cost (for example the asylum hotels which cost about £3bn a year) or where the money could come from (e.g. billionaires) and how much money the country actually needs if it wants to keep a state the size we have now and not cut anything.

The rich - rightly - already carry more of the tax burden than the poorest in society. But the UK now finds itself in a very precarious position with taxes on median workers actually low by historical standards and significant pressure on the highest earners. When 10% of your income tax is reliant on 0.1% of workers then clearly if they are pushed too far and decide to leave the country it opens up an eye-watering gap in revenues.

While screaming ‘tax the rich’ and thinking all our money can be found from ‘someone else’ is back in fashion, the truth that our politicians are not currently willing to say out loud is that the most reliable and highest revenue raising measures are ‘broad based’ i.e. take a bit of a wide group of people.

NI down, income tax up

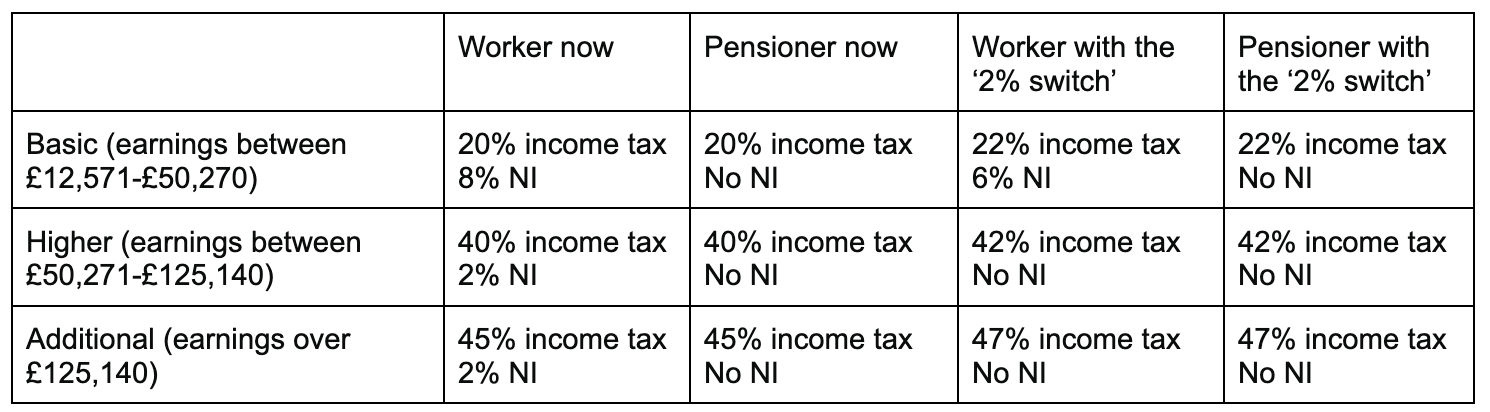

So why is the Chancellor reportedly planning to raise every income tax band by 2% and at the same time cut national insurance by 2% - ‘the 2% switch’. Why would she do this? Wouldn’t it cancel itself out?

The first misconception is that national insurance has some special ‘ringfenced status’ and goes directly into your state pension pot while also funding the NHS. This is complete nonsense. National insurance is just another tax which politicians of various stripes have pretended goes directly into the NHS or state pension - it doesn’t. It is also a tax not paid by those above state pension age.

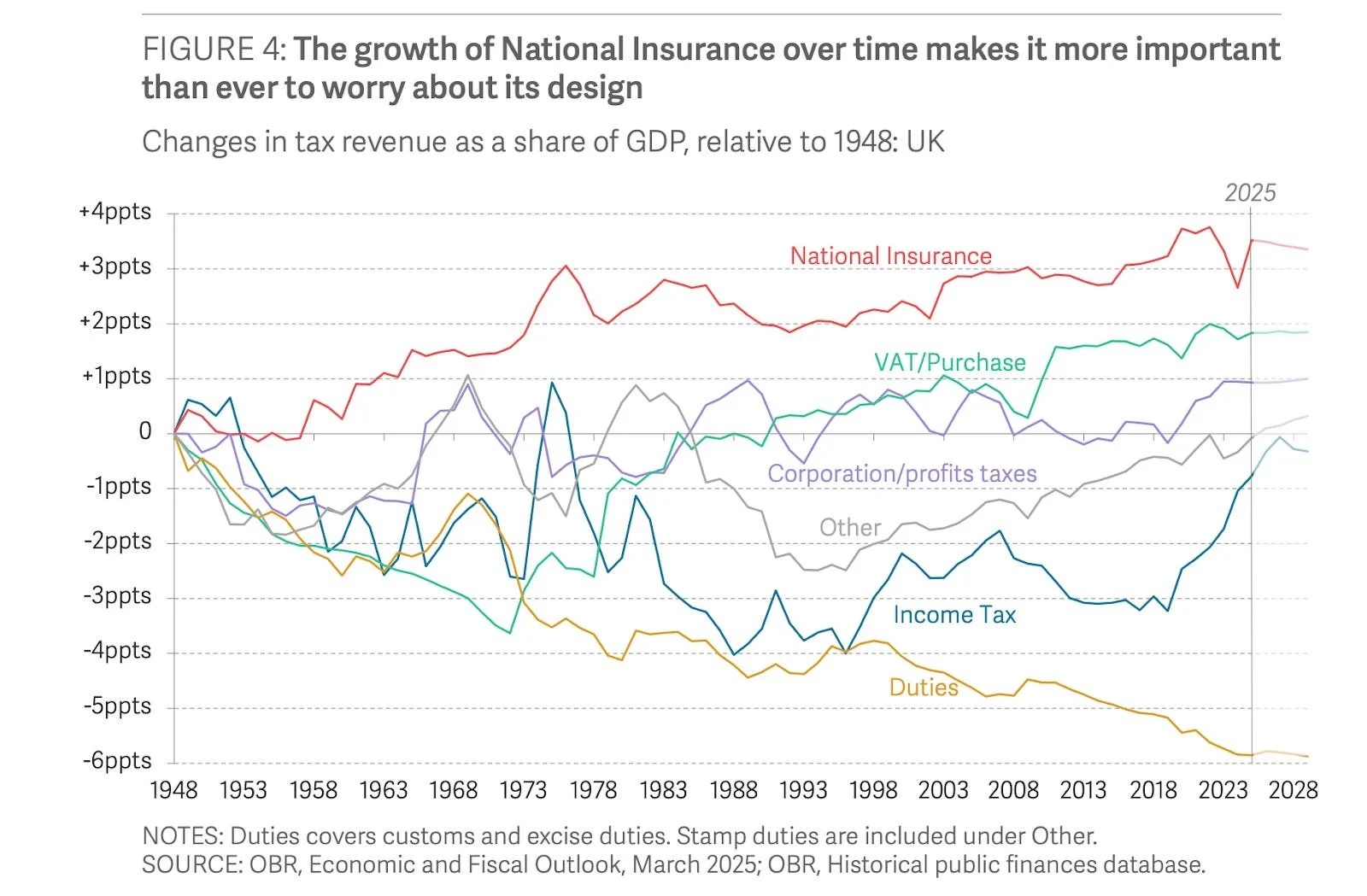

Because of sneaky political manoeuvring over the years, national insurance has also grown in importance by bringing in more and more revenue as a share of GDP. This means how it operates and who it impacts are more important. See the chart below from the Resolution Foundation.

National Insurance has grown steadily as a share of GDP since 1948. Source: Resolution Foundation.

According to the Office for National Statistics there are nearly 1.5million pensioners in work, past the state retirement age and hence not paying NI. This presents an attractive opportunity for a desperate Chancellor.

By raising income tax and cutting NI (the 2% switch) she can try to make the argument that she has broadly stuck to her manifesto promises (not to raise NI, income tax and VAT) because it would not impact most ‘working people’. It’s effectively a tax on pensioners who are still in work or earning substantially from their pensions/rental income and the self-employed.

The Resolution Foundation calculates that this 2% switch will raise around £6bn extra per year for the Chancellor while allowing her to try and argue (will be received with mixed opinions) that she’s kept to the spirit of her manifesto promises.

But when we follow the money, we know raising £6bn extra a year still leaves the government with as much as £30bn still to find.

Other likely and trialled measures that build on the 2% switch seem to be:

an increase in the national insurance paid by those who are members of LLPs (raises £2bn according to CenTax),

measures to reduce the amount of pensions contributions allowed via ‘salary sacrifice’ (raises £2bn according to government estimates),

and raising self-employment national insurance rates (could raise between £1-8bn depending on what measures are taken) and increasing the rates of dividend tax (raises £0.4bn per 1% rise according to the IFS).

All in all, taking the most optimistic estimates from a tax raising point of view, these measures would result in still needing to find around another £10bn in revenues.

Whether these come from either savings, or even more tinkering with the tax system remains to be seen. But until the decision is made, we will not be able to afford the public services we have gotten used to over previous decades.

Interested in how shifting tax and fiscal policy could affect your organisation or region?

Speak to our team about how Bradshaw Advisory can help you navigate the economic and policy implications of these changes.