Do Labour need to remind us that they’re really Labour?

Luke Downham, former Labour Treasury team adviser, on why the Spring Statement could be consequential for party unity.

Britain is broke. Public sector debt sits at 96% of GDP. The tax burden is on course to be the highest it has ever been. To compound things, growth - the number one priority for the Prime Minister and his Chancellor - isn’t on the near horizon either, with the Bank of England and now the OBR having halved their growth forecasts for 2025.

The Chancellor argues that things have changed. A fast-changing picture at home and abroad is why this week’s Spring Statement was more than the non-event she envisaged back in October. Her fiscal headroom since the Budget? Gone. Defence spending? Up.

Few in Westminster would argue that fiscal changes were not needed this week. But listen closely and you’ll hear a growing hum of discontent from inside the Labour Party about how the books are being balanced. Here are the top three highlights:

Headline cuts to out-of-work benefits - saving £4.8 billion (according to the OBR).

A paring back of the Civil Service by 2030 - yielding 15% savings in Government running costs.

A siphoning of £6bn from the aid budget to defence provides a welcome boost in fiscal headroom. Yet, this is not without political risks.

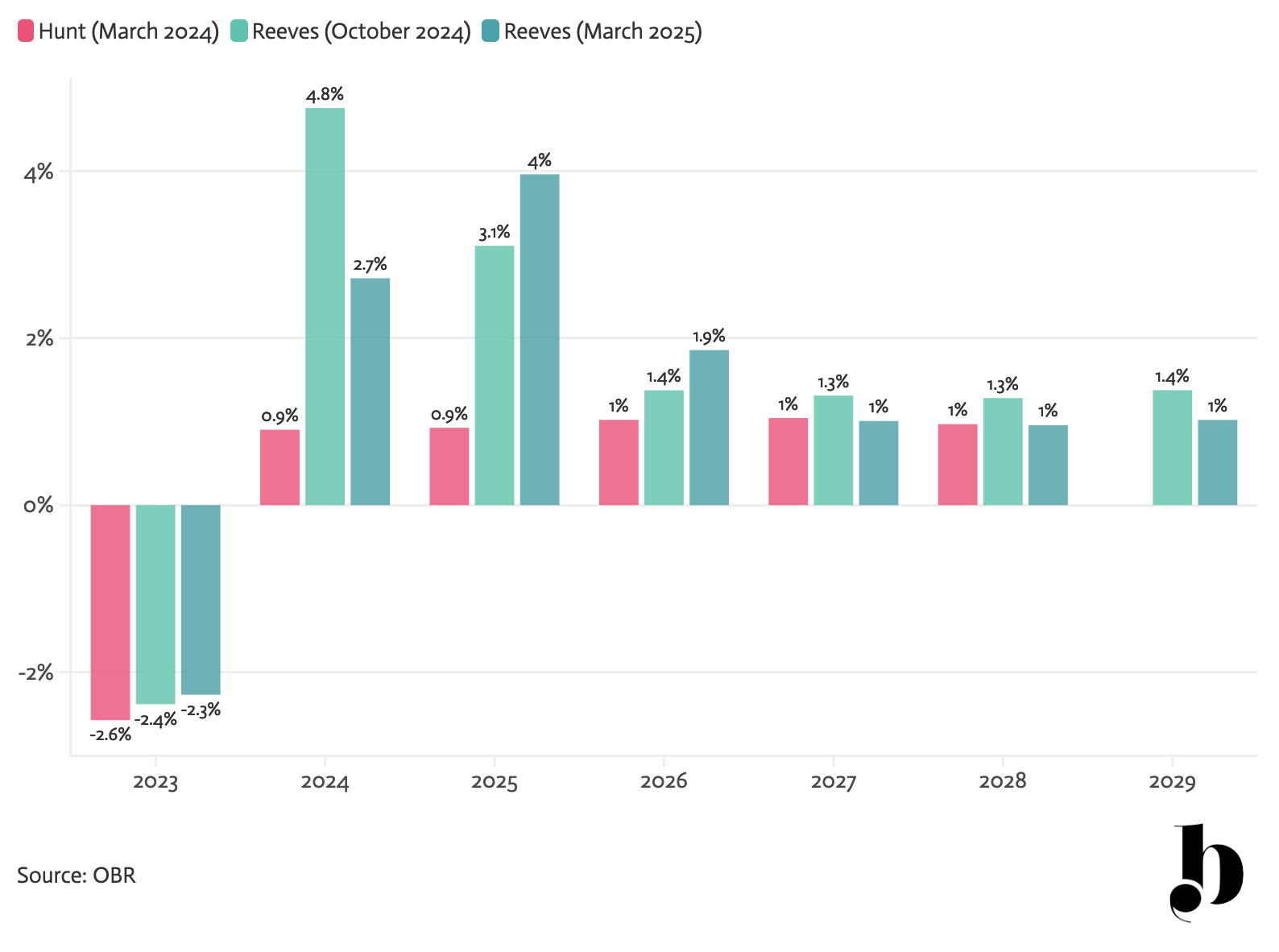

In better news for Labour MPs, day-to-day Government spending will be protected, rising above inflation in every year in the forecast period. Yet, today’s OBR forecast signalled a stagnant economy that may mean more difficult decisions in the Autumn Budget.

There is a whiff of Osbornomics in some of today’s language and measures. For a Chancellor who pledged “no return to austerity”, whilst championing the “difference a Labour Government makes”, there are implications for party unity approaching.

As a former adviser in the Labour Treasury team, I witnessed a party united behind Rachel Reeves. Yet, in recent months, that unity has started to crack. Despite Labour’s enormous majority in Parliament, after this de facto fiscal event things will become more fraught, and policy direction may see some adjustment.

Austerity 2.0? Not really.

The word “austerity” conjures memories of George Osborne and Danny Alexander on the steps of Number 11 before the Budgets between 2010 and 2015. What followed the short trip from Whitehall to the despatch box was deep cuts to public spending to reduce the deficit.

Labour for years dismissed austerity as an unforced error that choked off Britain’s recovery from the financial crisis. Anaemic growth, whether attributable or not to austerity, persists today. Yet, here we are, a Labour Chancellor cutting welfare spending during a period of low growth.

There are similarities between Osborne and Reeves, but there are subtle and not-so-subtle differences. Let’s take the similarities:

Both Osborne and Reeves are motivated by fiscal prudence and a willingness to make ‘tough decisions’ on the fundamentals of the welfare state. For instance, Liz Kendall’s reforms of disability benefits, to the tune of £4.8 billion per year by 2029-30, make for the single biggest cut to welfare than seen in any single fiscal event since 2015.

And the (many) differences:

The motivations of the coalition were very different to those of Reeves: cuts were designed to get public debt down quickly, rather than to plug gaps in the public finances.

In addition, there was simply more fat to trim in 2010, with the budgets of unprotected government departments making up 23% of spending in 2009/10. They only make up 11% in 2024/25 with ever more money going into (the unprotected) welfare, (and protected) health and education budgets.

Osborne made clear that a fiscal reckoning was needed to balance the books, whereas Reeves has been coy throughout her Chancellorship about the ultimate direction of fiscal policy.

Osborne was a political Chancellor to his core, ultimately believing in a small state. Reeves is more pragmatic than Osborne and believes in the “activist” state.

Whilst it is correct that the UK’s welfare bill is set to balloon to unsustainable levels by 2030 and beyond, even with these reforms, social security spending will continue to rise year-on-year in this Parliament.

Realising this, Reeves moved to cement cuts to DWP and the Civil Service quickly against the wishes of many of her backbenchers. The Chancellor would argue, however, that because she has committed to increase departmental spending above inflation, in no way can her measures be compared to the austerity years. She is right.

Figure 1: Real year on year spending growth under Jeremy Hunt and Rachel Reeves (Autumn and Spring forecasts, OBR)

That does not mean, however, that we are out of the woods. A return to healthy public finances will require economic growth. With poor prospects for the UK economy this year, the Chancellor may feel that she needs to intervene yet again in the Autumn. As my economist colleague Matthew Latham writes, that would mean coming clean with the public about the parlous state of the public finances, and the fiscal “trilemma” faced by the Treasury.

We likely haven’t seen the last of tax increases and spending cuts. Reeves, though, will be hoping her new found zeal for de-regulation (while introducing major new employment regulation) stimulates an uptick in growth, something the OBR is sunnier on from 2026 onwards, although what goes up often comes down at the OBR.

Red alert: Implications for party unity & policy direction

Whether you view the Spring Statement as a return to austerity or as a targeted and necessary cost-cutting exercise to balance the books, Labour have made a choice to govern somewhat out of character on the economy. At least that is the perception amongst the rank-and-file.

As I set out in my recent article on the Chancellor’s de-regulatory agenda, Labour’s turn on the economy marks a shift from the interventionist leanings outlined in her Mais lecture last year. A picture is now being painted of a Chancellor whose politics are based on the virtues of pragmatism and prudence.

The willingness of Starmer and Reeves to make ideological compromises to sustain the confidence of the markets on one hand and its voter coalition on the other is admirable. It is why Labour won the last election.

Yet, the cuts to welfare, winter fuel and international aid, in addition to delaying the reversal of the ‘Tory two-child benefit cap’, have angered MPs. Labour strategists consider these ‘tough decisions’ to poll well with the public, but while a good poll might get them through the week, will the public be satisfied with the impacts years down the line?

Public affairs professionals will wonder why this matters, but cracks in party unity are instructive of wider trends that could be developing.

Indeed, when questions are being asked about the substance of what the Labour Party fundamentally stands for, re-shuffles, resignations and policy U-turns are often not far off. The former Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls, hardly a leftist diehard, labelled the welfare cuts as “not a Labour thing to do”, underscoring the challenge.

Does the problem of definition highlight that the McSweeney policy agenda - fixed as always against the left of the party - is struggling to work out what it is actually for?

The implications of this approach to governing could be significant. Backbenchers, some of whom were elected only last summer, are querying what the difference would be if the Tories were still in power, beyond measures such as VAT on private schools and the employment rights package.

Keir Starmer’s grip on the party is iron-clad and he behaves ruthlessly in the face of dissent. But, for how much longer? Up to 80 MPs are reportedly considering whether to vote against the welfare reforms when the time comes. The whips will see to that, though, and the vote will pass.

The problem for Starmer and Reeves is not immediately dangerous, but fissures are beginning to show in Parliament.

Calls from the Labour left for one-off wealth taxes, or the re-introduction of the 50p top rate of tax to balance the books “more fairly” are punctuated by MPs on the right of the Labour Party who privately question the intellectual basis of a Labour government if it governs in a similar manner as the Cameroons.

These difficult questions will only grow more frequent after the Spring Statement. That could, for instance, mean pressure on the Treasury to reverse some of the cuts, raising the question of how that would be paid for.

Will the Chancellor feel she has to raid the coffers of the wealthy? Will businesses face further tax increases? Could there be cuts made to some departments to fund specific social policies? There are no easy answers.

Outputs from these tensions are already starting to show. Earlier this week, the Chancellor sought to placate MPs with a new £2 billion commitment to social and affordable housing, but this feels like thin gruel in comparison to the radical action that many think is needed.

In the end, all may be forgiven if growth shows up, but if it doesn’t, the Chancellor could soon be sitting amongst her critics on the backbenches.