US-EU trade deal: The 'least bad' alternative?

Who really 'won' (bigly) in Scotland? Bradshaw's Beatrice Gove has the details.

Donald Trump is now 86 away from his self-imposed target of 90 trade deals in 90 days. After rolling out a rather underwhelming - but still better than the rest - agreement with the UK earlier this summer, followed closely by thin trade deals in Japan and the Philippines, EU–US talks have now wrapped, sealed by a palpably awkward photo-op.

Von der Leyen's virtuous yet unconvincing smirk captured a humiliating compromise. A reminder that despite its "geo economic superpower" posturing, Europe still folds when Washington rears its orange head. Spanish PM Pedro Sanchez put it best: "I support this trade agreement... but I do so without any enthusiasm."

So what's in it? A 15% across-the-board tariff replacing the pre-Trump 1.2% where Brussels had once held out for zero, and until recently believed it might secure ten. The optics? A win for Trump, a blow to EU credibility, and more evidence that in 2025, symbolism trumps substance.

From 30% to 15%: a win?

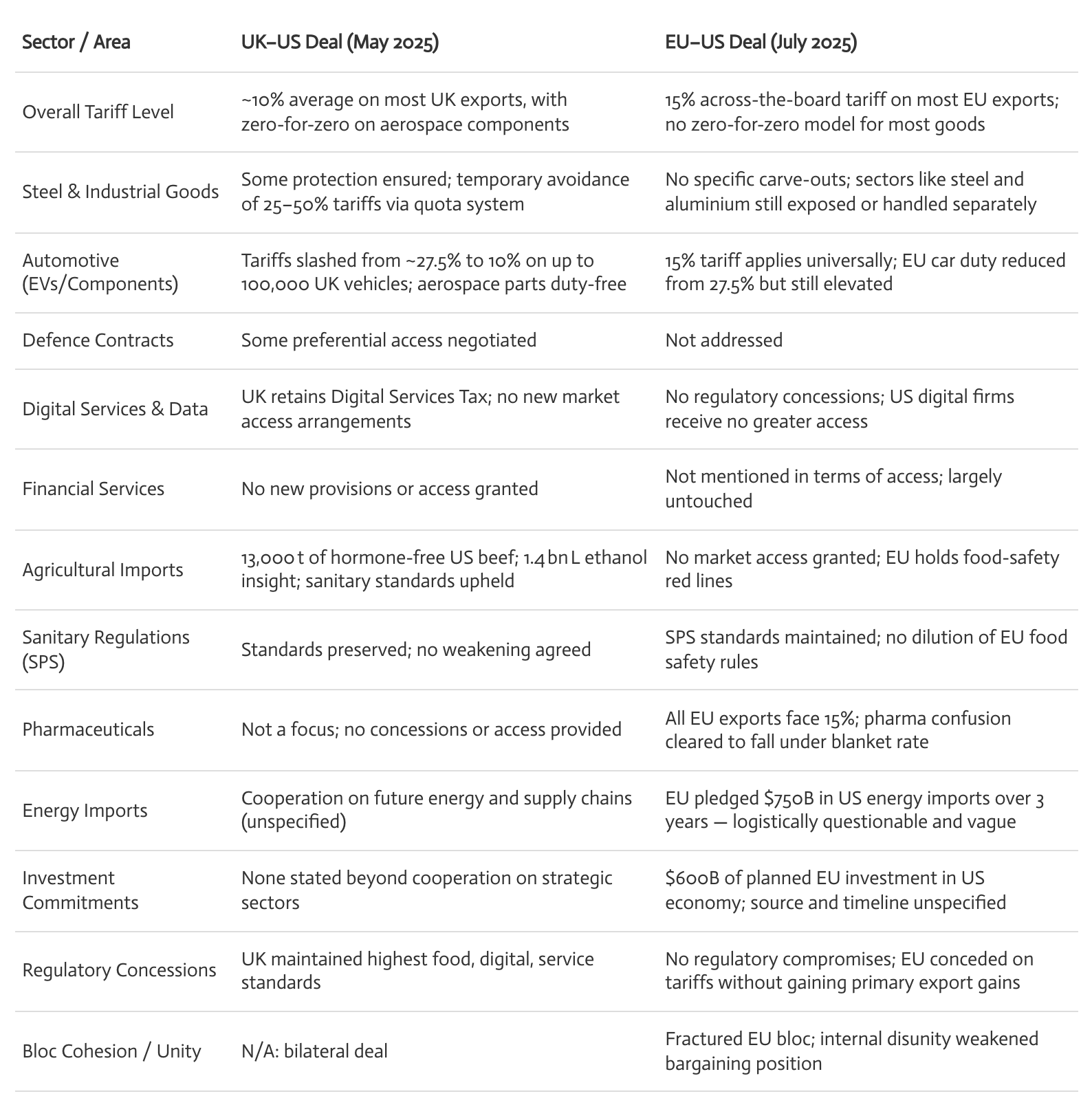

High-level summary of tariffs across key sectors from the latest US-UK and EU-US trade deals.

On paper, Brussels dodged disaster. Trump had threatened 30% tariffs on EU goods if no deal was reached by August 1st. They landed at 15%…though confusion lingered over whether pharmaceuticals were included, while EU steel will remain subject to the global goods-specific 50%.

Diplomacy prevails! But the best spin the EU could muster was "it could have been worse."

So why did Brussels fold? According to the Financial Times, the Commission initially proposed €26bn in retaliatory tariffs. Member states quickly whittled that down to €9bn. A more robust €72bn plan arrived too late and too divided to carry weight. With no unified position, Brussels had no leverage left. 15% was damage control. No reciprocal tariffs were levied.

Deal terms, or just vibes?

The EU pledged to buy $750bn worth of US energy over three years and invest $600bn into the US economy. The catch? No one seems to know how. Europe already buys over 50% of its LNG from the US. To hit those targets would mean a radical overhaul of oil, gas, and renewable procurement strategies

Gilles Moëc, chief economist at the French insurance giant AXA, dubbed the numbers "implausible," likening them to China's empty soybean pledges in 2018.

Trump gets to boast. The EU claims it had already planned much of the spending. Everyone forces a smile.

The regulatory fortress holds (just)

One quiet feature of this deal is what it omits. In his first term, Trump campaigned to pry open EU regulatory regimes. Particularly agriculture, digital services, and pharma. US firms have long seen Brussels as fortress-like. This was their chance.

Agriculture stayed untouched: no chlorinated chicken, no hormone-treated beef. But pharmaceuticals caused confusion. Trump hinted at higher tariffs. Von der Leyen insisted they were included in the 15%. “Whatever the decision later on is, of the president of the US, how to deal with pharmaceuticals in general globally, that’s on a different sheet of paper”, she said (not entirely reassuringly).

Eventually, US officials clarified: pharma exports face the standard 15%. Crisis (mostly) averted. Still, the EU now faces 15% tariffs on most goods, with no new access for US giants in return. Brussels can frame that as a defensive victory. They preserved their regulatory standards and provided no concessions on such a basis. But let’s not be so quick to mistake strategic restraint for a negotiating masterstroke.

The ‘best bad’ alternative?

The UK–US agreement, announced in May, was dubbed by Joseph Stiglitz, A Nobel Prize winning economist, as “not worth the paper its written on”. One wonders if he might re-evaluate such a statement given the EU’s comparative bruising. Britain, in hindsight came away with a far lighter landing. Most UK exports will face tariffs of 10%, a full third lower than those imposed on Brussels.

The Atlantic Declaration offered modest, yet meaningful progress: Tariff reductions on aerospace components and EV’s, preferential access to certain US defence contracts, and future cooperation on AI, energy, and supply chains. The UK also secured automotive export quotas, offering a small cushion for key industries, as well as a 25% tariff on UK-produced steel, half the global 50%.

Britain agreed to import 13,000 tonnes of non-hormone-treated US beef and 1.4 billion litres of ethanol, crucially holding the line on sanitary and phytosanitary standards. Chlorinated chicken will remain firmly off the table.

Whilst the UK's financial services and the Digital Services Tax did not get a look in, it is key to emphasise that Britain's deal, remains a comparatively ingenious totem of damage control. A tactically thought-through move on Starmer's behalf.

The jig is up

We are no longer in an age of free trade, if we ever really were. The European bloc has long defended its markets with regulatory walls. What has changed is not the protectionism itself, but the pretence.

Trump’s approach strips away the diplomatic veneer. His tariffs-as-tactics, optics-as-outcome strategy signifies a shift away from the long danced jig of toothless diplomacy. Tariff receipts quadrupled in May and with Biden having kept Trump’s first-term duties in place, there’s little reason to expect these new ones will vanish any time soon.

Europe blinks. Britain breathes.

Trump remains triumphant, average Americans less so. European businesses will struggle to absorb 15% tariffs, likely passing costs onto US buyers. Higher prices, disrupted supply chains, and weaker EU competitiveness to follow.

In contrast, the UK’s deal now looks much better than it did. Lower tariffs. Fewer bruises. A modest win for Starmer calcified by the 0.4% FTSE up-tick early this morning

But the most significant takeaway? The decisive blow to European solidarity. One wound made undeniably saltier by the UK’s comparatively comfy deal. Disunity dogged the negotiations from the outset, perhaps predictably, given that each member state faces very different levels of reliance on the US market and has varied strategic priorities.

Now, the deal must be ratified by all 27 EU member states. Some have responded with cautious approval, others with open scepticism. French officials have been notably critical. The ratification process risks exposing further fractures at a time when the bloc’s cohesion is already under strain.

The Atlantic declaration may not have been a revolutionary new deal unilaterally favouring the UK, but given the context of these so-called “trade agreements” – better understood as humiliation rituals– it stands up well. Europe emerged fractured, with little to no tangible concessions and a hefty 15% tariff, whilst the UK managed to resurface with lower tariffs, a FTSE bump AND concessions on major exports.

Contrary to the skeptics, I’m not inclined to reduce the UK’s deal to frail idioms. But if nothing else; this comparative analysis serves as a cautionary tale. A reminder of the classic Aesopean fable we are often too quick to forget.